Tracking Down Tuberculosis

Improvements in screening and diagnosis could help to eradicate this curable disease.

By Neil Savage

Mireille Kamariza is working on an affordable test for tuberculosis. Credit: Faranak Emami/Samueli School of Engineering, UCLA

Growing up in Burundi, a country of 13 million people in East Africa, Mireille Kamariza was familiar with the devastating effects of tuberculosis (TB). ‘It’s a long and torturous disease,’ she says. ‘You have relatives and loved ones that are sick, and you see them suffer through it. It’s not a quick death.’

When she moved to the United States at 17, she was struck by how different the situation was there. ‘The question that I had when I arrived here was, how come this is not a problem here?’ That question led Kamariza, now a chemical biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, on a quest to find ways to eradicate the disease in areas where it is widespread. A key challenge is determining who is infected, so that they can be treated and the disease stopped from spreading. But current diagnostic methods are slow, often expensive, sometimes difficult to administer and not easily accessible in the low-income regions where TB is most prevalent.

TB researchers are pushing to develop faster, more accurate and more accessible tests. In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) set the goal of reducing the number of new cases worldwide by 80% between 2015 and 2030; it considers widespread screening and rapid diagnosis as crucial to achieving this. Replacing older testing methods with newer diagnostic and screening techniques could help individuals with the disease to be identified quicker and start treatment before their symptoms worsen — potentially before they can spread the disease. ‘It’s the people who have TB and don’t know they have it, they’re the ones who are spreading the disease,’ says Jerry Cangelosi, an environmental-health scientist at the University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle.

TB has been infecting people for at least 9,000 years, and it has often been the leading cause of infectious-disease deaths globally. It was eclipsed in the past few years by COVID-19, but, as the pandemic wanes, TB could retake the top spot. According to the WHO, an estimated 10.6 million people caught TB globally in 2022 and 1.3 million died1.

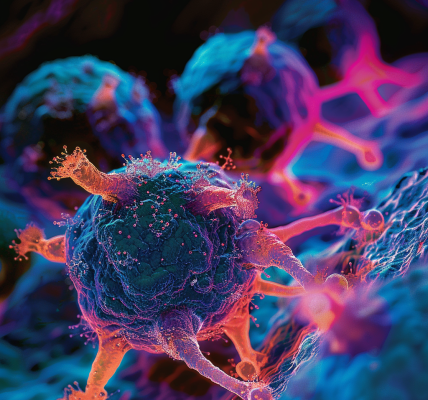

The disease is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a microorganism that is spread through coughing, sneezing and spitting. It thrives in crowded conditions where there is poverty, poor nutrition and a lack of accessible health care. Fortunately, the disease is treatable with antibiotics, and the drugs used now are less toxic and taken f