Recent research from Northeastern University sheds light on the complex nature of fear responses in the human brain, revealing that not all fears activate the same brain regions. This groundbreaking study, published in the neuroscience journal JNeurosci, indicates that the brain processes fear differently depending on the context of the fear-inducing situation.

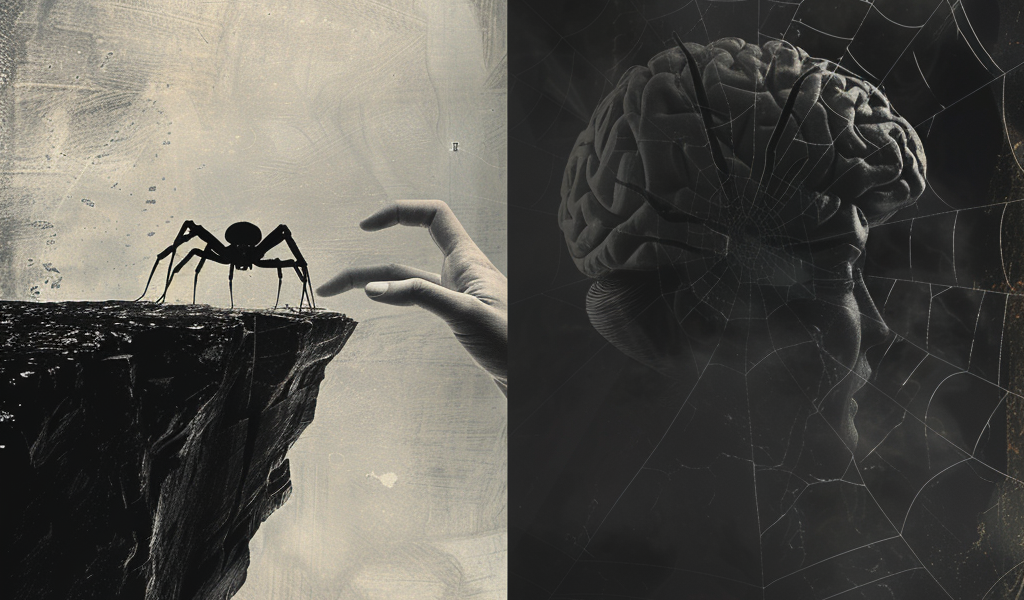

The study involved a sample of 21 participants who were shown a series of videos designed to evoke fear related to three specific situations: a fear of heights, a fear of spiders, and social threats. In total, 36 silent videos were utilized, each lasting between 18 to 22 seconds, and presented while participants underwent a functional MRI scan to monitor changes in blood flow and brain activity.

The researchers found that the majority of brain regions associated with predicting fear responses were only activated in certain contexts. They stated, “We show that the overwhelming majority of brain regions that predict fear, only do so for certain situations.” This suggests that the neural mechanisms of fear are not uniform but rather tailored to the specific type of fear being experienced.

To explore this phenomenon, the researchers selected fear-inducing scenarios that spanned a variety of properties. For instance, while many studies focus on fear in a predator-prey context, the fear of heights presents a unique challenge as it does not involve a direct predator. This distinction is crucial for understanding how different types of fear are processed in the brain.

The design of the study allowed for a systematic examination of the neural predictors of fear within each situation. Participants were asked to rate their expected fear levels before viewing each video, followed by a rating of their actual fear, arousal, and emotional valence after watching. This method provided insight into the subjective experience of fear and its correlation with brain activity.

Each video was carefully curated to evoke a range of fear responses. For example, in the fear of heights condition, a high-fear video depicted a first-person perspective of walking along the edge of a sheer cliff, while a low-fear video showed a person walking down a set of stairs. Such careful selection of video stimuli ensured that participants experienced a consistent psychological response throughout the experiment.

The immersive nature of the videos, shot from a first-person perspective, contributed to the realism of the fear-inducing scenarios. The researchers noted that the videos were designed to avoid dramatic changes or sudden ‘jump scares’ to maintain a stable psychological experience for the participants.

This research highlights the complexity of fear responses and suggests that our understanding of fear should consider the context in which it occurs. By examining the neural correlates of fear across different situations, scientists can gain deeper insights into how fear is processed in the brain, potentially leading to improved therapeutic approaches for individuals with phobias and anxiety disorders.

As scientists continue to unravel the intricacies of the human brain, studies like this one provide valuable information about the nature of fear and its impact on our lives. Understanding the specific brain mechanisms involved in different types of fear can pave the way for more effective treatments and interventions for those struggling with fear-related conditions.