A recent study conducted at Harvard Medical School has shed light on the inner workings of the brain’s internal compass and steering regions in fruit flies. The study, published in Nature, reveals how these two brain regions collaborate to guide the flies’ navigation and make real-time course corrections.

The research focused on understanding how the brain’s internal compass influences behavior. Despite extensive research on navigation in the brain, there has been a lack of clarity on how the internal compass directly drives behavior. The findings from this study provide valuable insights into this complex process.

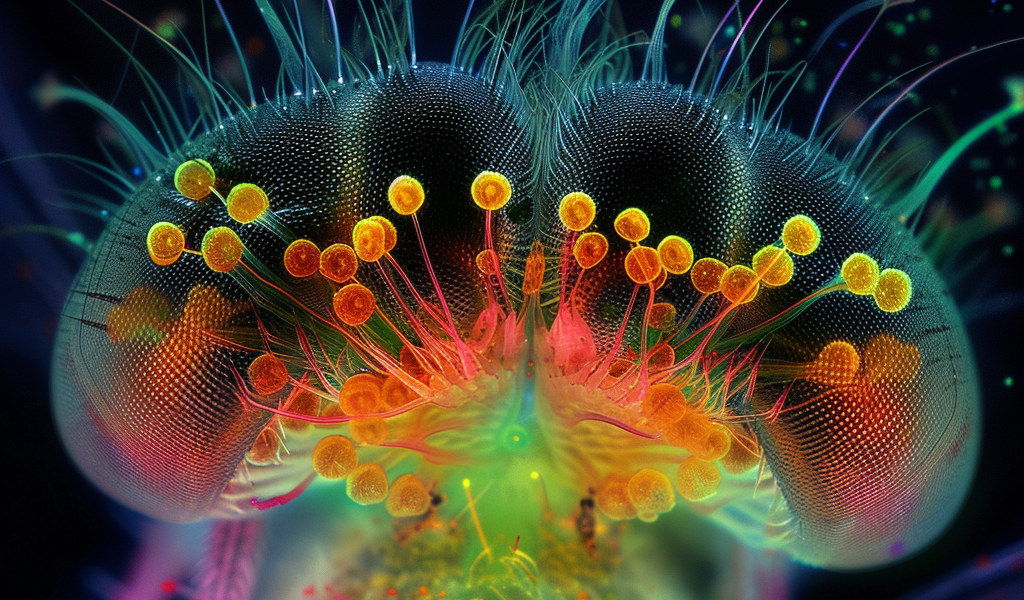

By examining the brains of fruit flies that were deliberately thrown off course while running in a specific direction, the researchers identified three distinct groups of neurons that facilitate communication between the compass and steering regions of the brain. These neurons work in tandem to assist the flies in correcting their course, effectively translating signals from the internal compass into behavioral adjustments to keep the flies on the right path.

Senior author Rachel Wilson, the Joseph B. Martin Professor of Basic Research in the Field of Neurobiology at HMS, highlighted the significance of the findings, stating, ‘Until now, no one really knew how sense of direction, which is an internal cognitive state, relates to the actions an animal is making in the world.’

Despite their small size, fruit flies possess complex brains and behaviors, making them an ideal subject for studying the interaction between the brain and behavior. The study’s implications extend beyond fruit flies and could serve as a foundational framework for future research on how brain signals translate into actions in more complex species, including humans.

In addition to shedding light on the brain’s internal compass, the research also delved into the organization of head-direction cells in fruit flies. These cells, responsible for generating a sense of direction, are arranged in a circular pattern, simplifying their study. The study emphasized that despite their name, fruit flies predominantly walk, and previous research has demonstrated the active tracking of rotational movement by these head-direction cells as the flies move around.