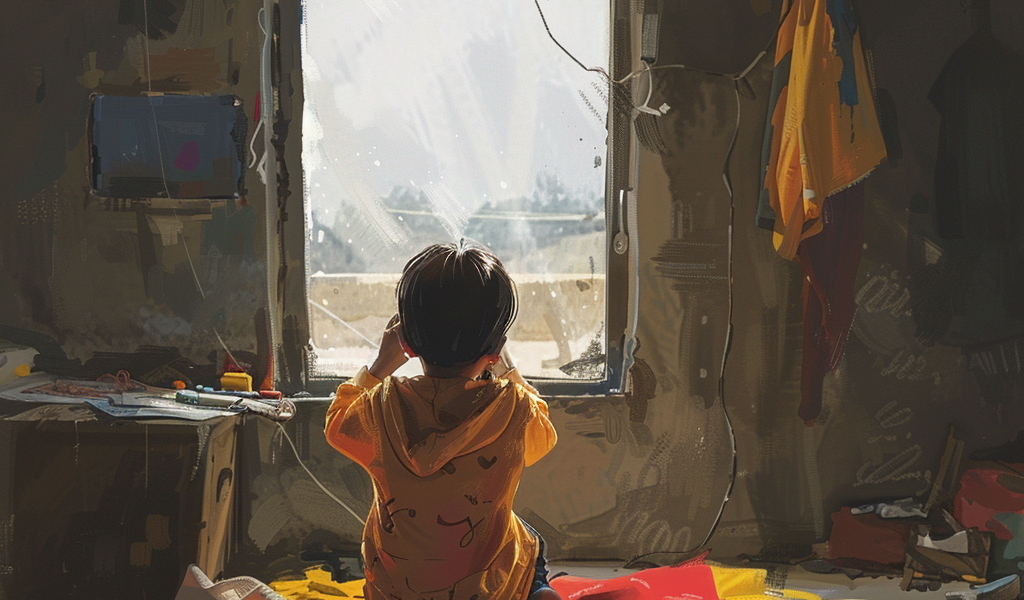

In a groundbreaking study conducted by the University of Surrey, researchers have discovered that telephone therapy can significantly aid refugee children grappling with mental health issues. The research highlights that therapy delivered via phone not only resulted in a marked decline in mental health symptoms but also showcased a higher completion rate compared to traditional in-person therapy sessions.

Led by Professor Michael Pluess, the study focused on 20 Syrian refugee children aged between eight and 17, residing in the Beqa’a region of Lebanon. The findings are particularly relevant given the increasing number of forcibly displaced individuals due to ongoing conflicts and humanitarian crises worldwide. Professor Pluess emphasized the urgent need for innovative solutions to provide effective mental health support in such challenging environments.

“The number of forcibly displaced persons due to war and emergencies is rising, and refugee children often endure severe trauma,” said Professor Pluess. He further noted that the research could pave the way for more accessible treatment options, as many refugees possess mobile phones, even in settings where mental health care is severely limited.

Lebanon currently hosts the highest number of refugees per capita globally, with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimating around 1.5 million Syrian refugees within its borders. The study’s implications are profound, as it addresses the pressing need for mental health services in regions overwhelmed by the refugee crisis.

The telephone therapy sessions were conducted in Arabic by trained local professionals, utilizing the Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA), which bears similarities to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). This method not only caters to the linguistic needs of the participants but also ensures cultural sensitivity in the therapeutic process.

In collaboration with Johns Hopkins University in the United States, the American University of Beirut, and Queen Mary University of London, the University of Surrey’s research underscores the importance of community involvement and local expertise in delivering effective mental health care.

Despite the promising results, the University of Surrey noted that fewer participants than expected came forward for the study. This was attributed to the stigma surrounding mental health services and a general lack of understanding regarding the nature of the treatment offered. Addressing these barriers is crucial for enhancing participation and ensuring that more children can benefit from such therapeutic interventions.

As the global community grapples with the ongoing refugee crisis, studies like this one shed light on the potential for remote therapeutic solutions to address the mental health needs of vulnerable populations. The findings advocate for a shift in how mental health services are delivered, particularly in humanitarian settings where traditional methods may fall short.

The impact of trauma on refugee children cannot be overstated, as many are exposed to violence, loss, and displacement at a young age. By leveraging technology, such as mobile phones, mental health professionals can reach these children in ways that are both accessible and effective.

As mental health continues to gain recognition as a critical component of overall well-being, the implications of this study may inspire further research and investment in innovative therapeutic approaches. The success of telephone therapy for refugee children could serve as a model for similar interventions in other crisis-affected regions around the world.

In conclusion, the findings from the University of Surrey’s study represent a significant advancement in the field of mental health care for refugees. By harnessing the power of technology and local expertise, it is possible to create a more inclusive and effective approach to mental health treatment that meets the unique needs of displaced populations.