Recent scientific studies suggest that body lice may have played a more significant role in spreading the deadly plague during the Middle Ages than previously thought. While rat fleas were known to be major carriers of the plague bacteria, Yersinia pestis, new research indicates that body lice could have also been efficient transmitters of the disease.

The debate surrounding the Black Death pandemic, which claimed the lives of millions in Europe, Asia, and other regions in the 14th century, has long focused on the mechanisms of transmission. While rat fleas were considered primary vectors of the disease, questions arose about whether their bites alone could account for the rapid spread of the plague.

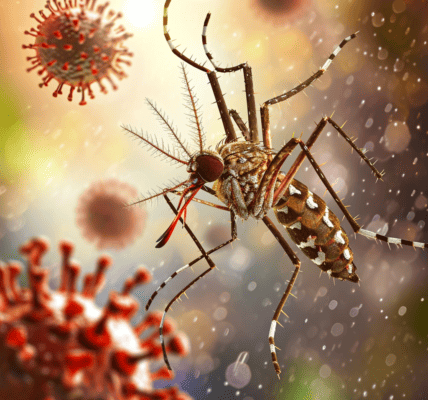

A study recently published in PLOS Biology shed light on the potential role of body lice in the transmission of the plague. Body lice, parasitic insects that thrive in crowded living conditions, are known to spread diseases among humans. In contrast to head lice, which are more common and typically affect children, body lice feed on human blood and can transmit pathogens.

Senior author of the study, Joe Hinnebusch, formerly of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Bacteriology, led the research that explored the transmission dynamics of the plague during the Middle Ages. The team initially investigated the role of human fleas in spreading the disease but found that they were not effective carriers of the bacteria.

Subsequently, the researchers focused on body lice and conducted a series of laboratory experiments to assess their potential as transmitters of the plague. The findings suggested that body lice may have been more efficient at spreading the disease than previously believed, contributing to the rapid escalation of the bubonic plague pandemic.

These insights into the transmission dynamics of the plague offer a new perspective on the historical events surrounding the Black Death and highlight the importance of understanding the role of different vectors in disease spread.